The Building

Opened to the public in 1940 with a corner stone date of 1938, 54 Jefferson was designed by Grand Rapids architect Roger Allen. It was one of the last projects to be funded by the W.P.A. in response to the Great Depression, and served as home to the Grand Rapids Public Museum until 1994.

Site Description

The interior is dominated by a great hall with terrazzo floor enclosed by a second floor balcony. The glass block windows shed a soft glow of light from the balcony level. A double staircase leads up to the windows and balcony. On both floors the great hall leads into exhibition galleries on the north and south sides. While the original dioramas (in most cases without the exhibited specimens) and display cases remain in most of the galleries, the galleries on the south side of the second floor were removed in the 1970s to accommodate the installation of new exhibits.

In 2000, following the museum’s relocation to a new facility, the Community Archives and Research Center, a state-of-the-art storage facility for the museum’s collection, was opened on a site to the east of 54 Jefferson. An atrium was also added to the rear of 54 Jefferson that connects the two facilities.

Building CAD files

Building Sketchup files

Download the Sketchup files for the building

Building History

A Brief Look at the Building History of the Grand Rapids Public Museum

In a twist on Winston Churchill’s much-quoted line, “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us,” it might be said that the Grand Rapids Public Museum has shaped its collections, and its collections have shaped its buildings.

The Early Years

When John Ball (a seminal figure in early Grand Rapids history) and a group of like-minded friends began meeting in the mid-19th century to discuss science and compare their collections, they stored their treasures in personal cabinets. The Wunderkammer, or Cabinet of Curiosities, had become the rage in Europe in the centuries following the discovery of the New World. Learned gentlemen of the 17th and 18th centuries, much more ecumenical in their interests than the specialists of today, often acquired and maintained large and diverse private repositories of fossils, rocks and minerals, preserved specimens of flora and fauna, relics of ancient cultures, oddities of nature, and anything that struck their fancy as worth further investigation.

In 1854 the Grand Rapids men decided to formalize their group, organizing as the Grand Rapids Lyceum of Natural History. In the agreement, several members offered to loan their “cabinets of Natural Curiosities” to the nascent museum. The Lyceum met and exhibited its materials in the city’s first high school.

The American Civil War brought an end to the Lyceum’s activities in 1860, and it lay dormant until 1865, when a group of high school boys revived the idea by starting the Grand Rapids Scientific Club. By 1868 their efforts had been so successful that the original group of men proposed a merger. Articles of Association were drawn up and the Kent Scientific Institute and Museum was born.

Years of success and setbacks followed for the new institution. Still housed at Central High School, they undertook ambitious projects, including involvement in the excavation of area Indian mounds, resulting in an impressive collection of relics which were exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876.

During this era, names of women also begin appearing in the archives of the museum. Emma Cole was the first person paid by the Kent Scientific Institute, spending many summers collecting “plants growing without cultivation” around the city, identifying and mounting thousands of specimens for their collection. She was named a Vice President of the Institute in 1900.

In 1901 the Institute turned over control of the collection and library to the Board of Education, which hired Herbert E. Sargent, Curator of the Museum of Natural History at the University of Michigan, as a consultant. In early 1903 the Board announced the purchase of the Howlett family home at the corner of Jefferson and Washington, to be converted into a museum, and appointed Sargent as its full-time director.

The First Museum Building

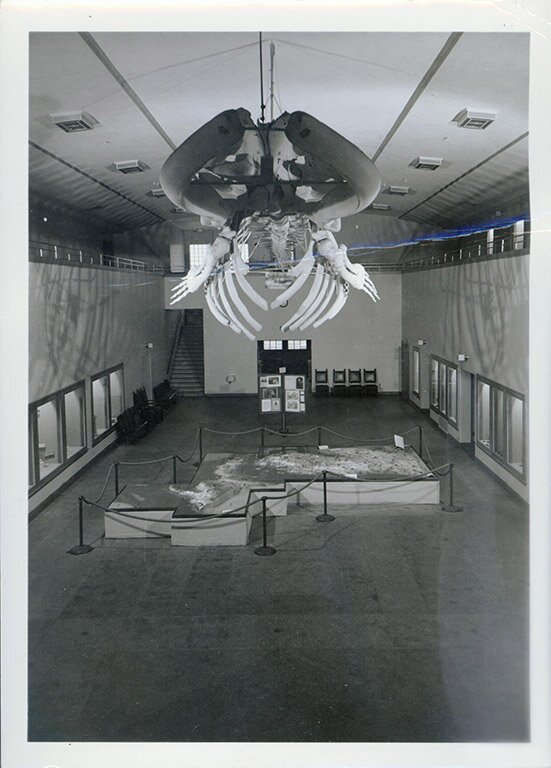

The three-story, mansard-roofed brick mansion was built in the 1880s by wealthy lumberman D.P. Clay. The main residence contained about 7500 sq. ft., and there was an outbuilding about half that size. Sargent embarked on a zealous campaign to fill the space, acquiring mastodon bones, an Egyptian mummy, and the 70-ft. skeleton of a finback whale. The latter necessitated the construction of a long low barn along the north side of the outbuilding, the first of many showcases for what has become one of the museum’s most beloved artifacts. In 1917, a house across the street from the main building was rented to accommodate the rapidly expanding collections.

By 1922, the board overseeing the Institute were becoming concerned with overcrowded exhibition space and asked Sargent to resign. They hired Henry L. Ward, former Director of the Milwaukee Public Museum, which had constructed a new facility during his tenure. He immediately embarked on a campaign for a similar endeavor in Grand Rapids, and in 1923 hired the Institute’s first Curator of Education, Frank L. DuMond, to expand its community activities.

DuMond (or Dewey, as he was known to friends) is a transformative figure in the Public Museum’s history. He held degrees in forestry from Cornell and Yale, and had worked in sawmills and lumber camps, and at Boy Scout camps, but had no background in museums. An article about him in 1978 reported that he had never visited a museum before applying at the Kent Scientific Institute. Perhaps that was a reason he was able to break free from many museum conventions and lead the organization into the modern era.

Among his first activities as director of the Institute’s education programs was to develop cooperative programs with local schools, improvising an auditorium in the old mansion for lectures that were filled to overflowing. His Saturday afternoon programs for children were so popular that Ward, in his appeals to the City to fund a larger space, described them as “mob conditions.”

Unfortunately, Ward was unable to bring his ambitious plans for a new museum facility to fruition. Ominous signals of economic decline led the City Commission to begin cutting the Institute’s allocations, and in 1932 they slashed it by 87%. Drastic staff reductions brought the resignation of Henry Ward, and Frank DuMond was named Acting Director.

For some leaders, the Great Depression turned into opportunity for progress and reform, and DuMond was one of them. An old automobile garage near the Museum had been rented for storage, and when the City decided to shutter the old mansion to save money, DuMond rose to the challenge by transforming the former Nash showroom into a popular public space and continuing an ambitious schedule of activities.

The Miracle on Jefferson Avenue

When the Institute moved back into the gloomy, cluttered old residence in 1935, DuMond declared, “Our success in drawing record-breaking crowds into the State Street garage has taught us that accessibility is important. If Grand Rapids should ever find enough money with which to build a new museum I suggest it be brought out to the sidewalk line at street level and be windowless except for a few openings to attract the attention of passersby.”

It would take many years of determination and creative fundraising (in an unpublished memoir, DuMond titled the section on the campaign, “A Miracle Happens”), but when a new building, now dubbed the Grand Rapids Public Museum, opened in June 1940, those ideas were apparent in its every aspect.

The design of the new Museum at 54 Jefferson, on the site of the demolished mansion, was not just reflective of DuMond’s experience in the old auto showroom. It was an era of changing attitudes toward architecture and its role in public life. While the roots of modernism may be traced to the sociological and technological changes of the Industrial Revolution, it was the mid-20th century before many American architects began to reject the nostalgia of classical forms and embrace the machine age.

A fresh style began to emerge, focusing on a building’s function and exploiting the qualities of industrial materials and technological advances. Frank DuMond was not the first to apply these ideas to museums. In 1926, John Cotton Dana, director of the Newark Museum in New Jersey, commissioned Chicago architect Jarvis Hunt, who had also completed a Macy’s Department Store in Newark, to design what would become the first modern public museum building in the country.

Closer to home, ideas about modern design were percolating. In 1930, New York industrial designer Gilbert Rohde convinced D.J. DePree, the president of West Michigan furniture maker Herman Miller, of the virtues of modernism, launching a revolution that would result in work by some of the most significant designers of the 20th century. In 1937, architect Frank Lloyd Wright commissioned the Metal Office Furniture Company of Grand Rapids, forerunner to Steelcase, to manufacture his radically modern furniture for the office building he designed for S.C. Johnson & Son in Wisconsin. Eventually, ideas crafted in West Michigan about office space and office furniture design would change the way people work all over the world.

Grand Rapids architect Roger Allen, a member of the American Institute of Architects and President of the West Michigan Society of Architects, was chosen to work with DuMond’s ideas to design the new museum. He was chosen in part for his knowledge of projects financed by the WPA, from which much of the funding for the new museum was to come. The design came to be widely known as the Grand Rapids Plan, an essentially windowless two-story structure of reinforced concrete, with a street-level entrance brought right up to the sidewalk line and five display windows set in walls facing Jefferson and Washington streets.

Grand Rapids architect Roger Allen, a member of the American Institute of Architects and President of the West Michigan Society of Architects, was chosen to work with DuMond’s ideas to design the new museum. He was chosen in part for his knowledge of projects financed by the WPA, from which much of the funding for the new museum was to come. The design came to be widely known as the Grand Rapids Plan, an essentially windowless two-story structure of reinforced concrete, with a street-level entrance brought right up to the sidewalk line and five display windows set in walls facing Jefferson and Washington streets.

1952

The new Museum drew national attention. A full-page article in The Christian Science Monitor on December 23, 1941 featured the new building and its exhibitions and quoted DuMond’s dream of a new type of museum which would be, as the article headline stated, “As Accessible as a Dime Store, as Friendly as a Next-Door Neighbor.”

The new building also featured new ideas about exhibition techniques. Most of the exhibits in the mansion-turned-museum were of the old-school ‘parlor collections’ assembled by the 19th-century founders, displayed in large wooden and glass curio cabinets. Ward had brought an innovation with him from the Milwaukee Museum, the habitat diorama, and DuMond embraced the idea with gusto in the new facility. He also introduced recessed display cases built into gallery walls, and department store style display windows.

Growth and More Growth

DuMond would make the most of his cherished new building. Over the next decades the Museum was deeply involved in the life of the community. The coming of World War II prompted renewed interest in patriotism and the roots of America, reflected in programs and exhibitions. In 1958, the City acquired an old building just east of the Museum, increasing exhibition space and providing a site for a Planetarium. DuMond’s final project as director was to create an elaborate building connecting the two structures, lined with an indoor street of shops evoking the gaslight era of old Grand Rapids.

While DuMond stayed on past retirement to complete his pet project, the Museum named Weldon D. Frankforter as Director in 1965. The energetic young geologist and paleontologist had been hired as Assistant Director in 1962. A member of many national organizations, Frankforter helped establish the Grand Rapids Public Museum as one of the country’s urban museum success stories. In May 1970 the first Michigan Historic Preservation Conference was held in Grand Rapids, co-sponsored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. At the conference it was announced that the Public Museum would be part of the first group of institutions to be evaluated by the American Association of Museums, a national organization founded in 1906, for a new program of accreditation that would signify that a museum had met national standards established by the museum profession. The Grand Rapids museum was chosen as a test case, and in 1971 became the first to be accredited.

Over the years the Museum would assume responsibility for a number of Grand Rapids landmarks, including Blandford Nature Center, the Voigt House Victorian Museum, the Norton Indian Mounds (now a National Historic Landmark) and the collection of the Grand Rapids Furniture Museum. Some of these are still in the purview of the Museum, others have become independent organizations.

A Cabinet of Wonder on the River

More than a hundred years after John Ball and his friends founded the Lyceum of Natural History, the Grand Rapids Public Museum was outgrowing its capacity to maintain and display the enormous collections that had blossomed from those original Cabinets of Wonder. In 1976, the Museum purchased its first building solely dedicated to collections storage, a building on State Street just southeast of the main Museum that came to be known as the Attic. Ironically, it was the same building that Frank DuMond had leased some 40 years earlier to house the Museum more economically for three years during the Depression.

But that facility, and the East Building addition acquired in 1958, were both bursting at the seams with 120 years of collecting. The new storehouse would address some problems temporarily, but it was clear that a long-term solution for better access and display was needed. The Museum once again launched into the process of planning and constructing a new building.

Planning began in 1977, but it would again take many years of determination and creative fundraising to bring the new facility to life. Timothy J. Chester was appointed as Assistant Director in 1986 and became Director in 1988, faced with the immediate task of rallying the somewhat demoralized group of staff and volunteers who had been working on the project for more than ten years.

The new museum on the Grand River opened on November 19, 1994. Van Andel Museum Center was designed to reflect the architectural heritage of West Michigan, incorporating historically appropriate materials and details. Exterior bands of burnt orange and red brick set against cream was a common motif in 19th-century Grand Rapids, and also references the building traditions of Dutch immigrants. Situated directly on the river at the site of the old Voigt Crescent Flour Mill, the structure’s mass celebrates its predecessor as well as the factories and mills that once lined both banks of the Grand River to harness its water power.

The Design Architect for the project was E. Verner Johnson & Associates, with Lawrence Man as Consulting Architect and Building Graphics Designer, and The WBDC Group/Beta Design Group, Grand Rapids architects.

The Museum Center also was designed to take advantage of its riverfront location, the changing light reflected from the water and the view to and from the heart of the city across the open expanse. During the day huge windows frame spectacular views, and at night the Museum’s key treasures are illuminated from within.

Clearly visible from outside the building are many of what the community has come to recognize as the Museum’s icon objects: the finback whale skeleton, undulating above the main gallery as if somehow making its way up the river; the 1928 Spillman Carousel, suspended over the river in its own pavilion, a marvelous feat of engineering and sensitive design; the E. Howard tower clock from the 19th-century City Hall, torn down during the urban renewal fervor of the 1960s.

What Do We Do With This Stuff?

One of the biggest decisions about Van Andel Museum Center was not to put collections storage on-site, as was originally planned. The decision helped clarify thinking about the old Museum building on Jefferson Avenue.

In April 1998, Tim Chester announced that a collaborative team including the City Manager, City Clerk, County Clerk, and Museum staff was researching the creation of a center to house community archives and the Museum’s unexhibited collections. The process was completed by July 1. The result was an ambitious two-phase, long-term plan, first for the site of the former East Building, and a West Phase for the WPA-moderne building at 54 Jefferson.

Shortly after the plan was devised, Chester received a phone call. The Michigan Department of Transportation was in the middle of final routing plans for reconstruction and improvement of the U.S. 131 expressway in downtown Grand Rapids. The most recent design ran right through the Star Building, the Museum’s current collections storage, and M-DOT was calling to see if they could vacate the building in 15 months. With compensation from M-DOT for the cost of relocating the collections, it was possible to fast-track the first phase of the plan.

And fast track they did. Demolition crews moved in at the old Museum East Building site at the beginning of 1999, and by mid-July, 2000, the collection was safe in its new home.

Now What?

With the first phase, the Community Archives and Research Center, complete, the Museum paused. The second phase, what to do with the old building at 54 Jefferson, was not as clearly defined by need as the splendid new collections storage facility. Timothy Chester left the Museum in 2006 and Mary Esther Lee became the first woman to lead the organization. She retired in 2009 and Dale Robertson became President and CEO.

Many ideas had been vetted in the planning process for the former Museum site, but the economic climate and changes in museum structure have been obstacles to using the 1940 building. It was used for storage until April, 2010, when it was repurposed for Michigan: Land of Riches, an exhibition that invited local artists and students from area art programs to re-examine the old museum building and respond to its architecture and remnants of old displays. Led by curator Paul Amenta, the event was wildly successful.

Since 2007, Amenta and his team had been staging events in the Grand Rapids area that encouraged artists to respond to venues, either formally or conceptually. Now known as Site:Lab, the group creates temporary site-specific art projects aimed at facilitating dynamic collaborations between the art, education, business and cultural communities of Grand Rapids.

Site:Lab returned to 54 Jefferson in September 2012 as part of ArtPrize, hosting 18 projects and winning the juried prize for best venue.

The 2012 project was titled The Dream Before, referencing a Laurie Anderson song from her 1989 album Strange Angels. In The Presence of the Past, a book on the Museum’s history published in 2004, lyrics from that song, which is dedicated to the early 20th century German writer Walter Benjamin, are used to convey the poignant feeling of the T.S. Elliott quote that gave the book its title: “time present and time past … both perhaps present in time future and time future contained in time past.” Her words paraphrase a Benjamin passage describing a painting by Paul Klee, written, coincidentally, in 1940 when the then-modern building at 54 Jefferson opened:

“What is history?

History is an angel

being blown backwards into the future

History is a pile of debris

And the angel wants to go back and fix things

To repair the things that have been broken

But there is a storm blowing from Paradise

And the storm keeps blowing the angel

backwards into the future

And this storm, this storm

is called

Progress.”

(This brief look at the buildings of the Grand Rapids Public Museum was compiled by Julie Christianson Stivers from her book, The Presence of the Past, published in 2004 as part of the Museum’s 150th anniversary celebration. It is available in the Museum’s gift shop.)

Thank you to Alex Forist for the images

The Neighborhood

by Tom Logan

The old Grand Rapids Public Museum building on Jefferson Avenue is a symbol of continuity, change and stability in its neighborhood:

- it succeeded a Victorian house which held the collections of its predecessor–the Kent Scientific Institute–on the same site;

- it followed and continued a process of change from residential to commercial and institutional land uses;

- it remains a landmark which defines the relationship of the historic neighborhood up the hill with the institutions south of the city’s “downtown”;

- it still stands and benefits from much public support to be preserved as a community resource.

Around the turn to the 20th century, the area was platted and developed as a residential area south of the original city plats. In the 20s and 30s it became the city’s first “auto row”. There are still several buildings within 2 blocks of the old museum which were built as auto dealerships or service establishments. Also starting in the first decade of the 20th century and continuing today, major institutions have spread their influence and their land holdings to replace both residential and commercial properties of earlier times. These include two hospitals and other health institutions, the Catholic cathedral, high school and diocesan buildings, and several other churches. Several streets have disappeared in the process, interrupting the regular grid plan of the original plat. The character of State Street, connecting the museum location with the heart of the historic Heritage Hill residential area, has changed several times as well. Today the neighborhood association and others seek to generate a revival of a State street with active land uses and a renewed sense of place.

The museum building is also historically important for its style of architecture: the modern, Art-Deco style of the building was an important one in the 30s and 40s, but never had many manifestations in Grand Rapids. Of those few, most have disappeared in later redevelopment. The old museum is a restrained and elegant example of this important chapter in architectural history.

Tom Logan is the author of Almost Lost – Building and Preserving Heritage Hill Grand Rapids, Michigan

Access

It may be possible for entrants to arrange a tour of 54 Jefferson. Contact for information.